Saturday afternoon on 13th February 2021 and the weather is bitterly cold as the weather front dubbed ‘The Beast From The East 2’ delivers its last blasts of cold air. However, the sun is out and the brightness makes the temperature much more bearable. Having been housebound for much of the week, for work rather than health reasons, I decided that I must make an effort and get some exercise that would get both my good and bad knee moving.

I had been told that the the lychgate of St Mary the Virgin in Birchanger, a village just outside of Bishops Stortford, bore the green and white plaque that indicates that the churchyard contains Commonwealth War Grave Commission plots and this was reason enough for me to head off in that direction.

There is a war memorial to the men of the parish who fell in the two world wars but I could find no individual soldiers graves. I will look again at some point soon. Crunching my way across the frozen earth that was doing its level best to hold on to the snow that fell at the beginning of the week, I entered an area of the graveyard that had seemingly in the past been sectioned off by the planting of trees. These served to create natural sanctum almost, screened away from the rest of the churchyard. A look at the headstones close by indicated that this would indeed have been intentional as within this shielded green space were the plots of various members of the Gold family, prominent local people, including Sir Charles Gold, the onetime Liberal MP for Saffron Walden and Walter Gilby’s (he of the alcoholic beverage fame) brother-in-law.

Close by the title heavy headstone of Charles Gold, Knight Batchelor, is a small unassuming memorial headstone, the lettering of which although badly worn can still be read.

The war lasted nearly two and a half years with the death of Lieutenant Watney occurring in the last months of the war at a time when the Boer commandoes were fighting a series guerilla actions against the British forces, now present in great number. The Boers finally surrendered in the face of deployment of a scorched earth policy that destroyed their farmland and incarcerated civilians in concentration camps where many thousand succumbed to starvation and disease.

One such guerilla raid on Colonel Firman’s Brigade was led by the Boer commando of Christiaan de Wet. The Brigade were deployed in the construction of a series of blockhouse fortifications over the 50 mile distance between Bethlehem and Harrismith (shown on the map). These blockhouses connected with barbed wire stretched across large areas of the veldt (the grassland plains) were intended to restrict the movements of the Boer fighters such that the British forces could systematically eliminate them. At Christmas 1901, the Brigade were camped the reverse slopes of the Groenkop, a small hill on an otherwise flat plain.

Contemporary reports of the fighting featured in many newspapers in the UK, the successes enjoyed and indeed the calamities endured by the British Army were read with keen interest by a public buoyed by Empire stories. Earlier in the war, the relief of the garrison town of Mafeking was a cause for great celebration in Britain’s streets.

4th January 1902

Lord Kitchener on Sunday morning telegraphed from Johannesburg that the prisoners in De Wet’s attack on Colonel Firman’s camp on Christmas morning have been released, and have arrived in Bethlehem. In a previous message he has sent some details of the mishap. The column was encamped on the slope of a solitary kopje, the southern side of which was almost precipitous. Up that side the Boers crept and collected near the top.

At two in the morning they suddenly attacked the piquets on the summit, and before the men could get clear of their tents the Boers rushed through, shooting them down as they came out. There was no panic, and all did their best, but the enemy, who apparently numbered 1200, were too strong, and once the piquet was overwhelmed they had all the advantage. The casualty list shows that six officers and 50 men were killed, including Major G. A. Williams, who, in Colonel Firman’s absence, was in command; eight officers were wounded, and four others were missing.

Two officers who were in the camp after the fight, state that dead Boers were lying all over the ground at daylight, and two wagon-loads of dead and wounded Boers, mostly hit in the first attack on the piquets, were taken away.

On the news of the reverse reaching Elands River Bridge, 14 miles distant, the Imperial Light Horse hastened to the scene, which was reached at 40 minutes past 6, and afterwards galloped after the Boers, without overtaking them. When the enemy reached Langburg, Lord Kitchener adds, the Imperial Light Horse could do nothing more against superior numbers in such a country.

THE FIGHT AT TWEEFONTEIN

The strength of the Tweefontein

garrison so disastrously surprised by the fighting burghers under De Wet at

Christmas, must from a careful collection of accounts have been about 500

against 1200 Boers. The reverse was the result of a sudden concentration of

commandos under General De Wet.

General De Wet’s concentration of between 1500 and 1200 men in the north-east of Orange Colony has (according to a dispatch from Mr. Edgar Wallace, the Daily Mail war correspondent at Pretoria) been known for some time. These remnants of the best fighting blood of the old Free State, under dashing leaders, have been hovering about our small mobile columns operating from Harrismith and Heilbron, waiting for an opportunity to attack, while General De Wet himself, with 800 men, remained in the vicinity of Tafelkop and Ritz, ready to throw his support whenever it was required. Colonel Damant’s and General Dartnell’s fights were the result of this policy, but the columns made up for their attenuated condition by extreme mobility and caution under clever and tried leaders able to inflict severe punishment on the enemy. The last incident near Harrismith seems, however, to have been altogether in favour of the enemy. It shows the completeness of their intelligence service and their ability to suddenly concentrate. It appears to be time (sapiently says Mr. Edgar Wallace) that the system of moving bases was extended to all the mobile columns, leaving the best mounted men at liberty to make raids unencumbered by transport, thus creating troops as mobile as the enemy and a hundred times more dangerous.

Lieutenant Jack Southard Watney, 11th Battalion Imperial Yeomanry, who was killed while leading the charge at Tweefontein, was 19 years of age, and educated at Eton. Joining the Honourable Artillery Company in 1899, he went out to South Africa in February of last year with a draft from that company. At the time of his death he was in command of the Maxim gun attached to the 11th Battalion of the Imperial Yeomanry.

Tweefontein is situated in a mountainous country about equidistant from Bethlehem and Harrismith, which are some 60 miles apart. At no great distance to the south-west lies the Brandwater Basin, where De Wet was nearly cornered by General Rundle some 15 months ago, and away to the north – 50 miles or so- is Tafelkop, the scene of Colonel Damant’s severe engagement on December 20.

Of the man responsible for the planning of this guerilla raid, General Christiaan De Wet, the press are remarkably complementary!

Since the caging of Cronje and the death of Joubert the most considerable personality amongst those arrayed in South Africa against the might of Britain has undoubtedly been that of the marvelously mobile Christiaan De Wet – despite the superior fighting rank of Botha, the Commandant-General of the Boer forces.

Within an hour after the telegraph wires of the Transvaal flashed the word “oorlag,” meaning “war,” in October 1899, Christiaan De Wet had dropped his spade in the dam he was building on his farm and was riding across the veldt to go to battle. He knew little of the actuality of fighting then, but to-day he has the record of harassing the British Army as it has never been worried before. He has made dashing raids, time after time, and has attacked with fury forces five times as large as his own.

Cool, fearless, resourceful, a master in strategy and mobilising, for many months he was never surprised. When all odds were against him, he eluded Kitchener; he cut off Lord Robert’s communications by railway and telegraph; he slipped through Hamilton’s fingers in most irritating fashion and he outwitted Methuen by his so-called “Mosquito” tactics. This rough, untrained farmer has been the cause of many of the unfavourable telegrams sent by British Generals to the War Office. His tactics have received high praise from military experts, and he has been largely responsible for prolonging what has proved the campaign.

General De Wet is about forty years of age, of medium height, slight in build, with a sharp face, dark Moustache, and rough beard tinging slightly with grey, and a firm mouth, expressive of the dauntless determination which is one of the alert Boer guerilla leader’s strongest points.

Here's what he really looked like.

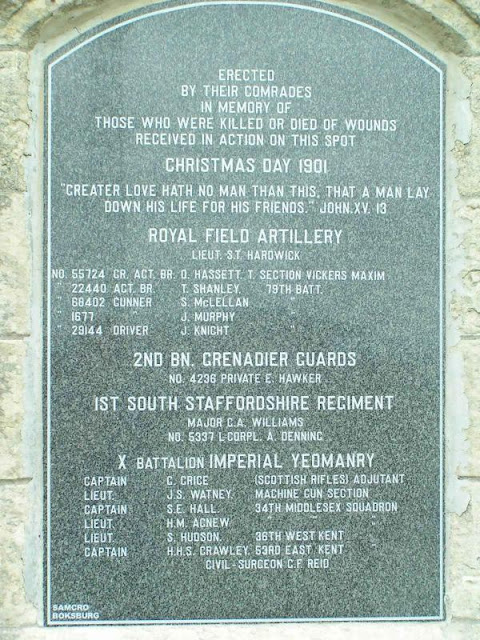

A memorial to the British dead from that Christmas Day 1901 stands at the camp site at the Tweefontein farm and Lieutenant J.S. Watney is commemorated on one of the panels.

No comments:

Post a Comment